August 30, 2017

Tragedy of the Snake River Commons

The law locks up both man and woman

Who steals a goose from off the commons

But let’s the greater felon loose

Who steals the commons from the goose.

Old English Proverb

A Tragedy Unfolding

In his 2005 bestseller Collapse, Jared Diamond describes how civilizations can quickly end when natural resources have been pushed to the limit, and then disaster—like a prolonged drought—sweeps across the land. For threatened and endangered salmon on the Columbia and Snake Rivers, 2015 was a disaster. An estimated 250,000 Columbia and Snake River adult sockeye salmon died before reaching spawning grounds due principally to high water temperatures. Only 56 Idaho sockeye reached the Sawtooth Basin, while 35 more were trucked from the lower Snake to the hatchery in Eagle, Idaho. Was 2015 a perfect storm of low water volume and high ambient temperatures, or are sockeye and other Snake River salmon and steelhead species now on an irreversible path to extinction?

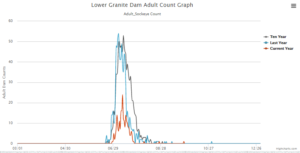

Snake River Sockeye

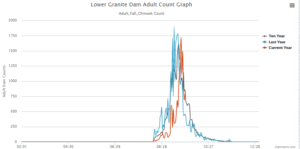

In 2015 the survival rate for juvenile Snake River sockeye from Lower Granite Dam to Bonneville Dam was just 32%. In 2016 that rate fell to 12%. Those survival rates do not include further losses below Bonneville Dam due to avian predation and delayed mortality. During 2015 and 2016 a total of 44 wild sockeye returned to Stanley Basin. This year only 227 adult sockeye passed Lower Granite Dam, and as of August 16 a total of 53 sockeye had returned to Stanley Basin fish traps, only 8 of which were wild fish.

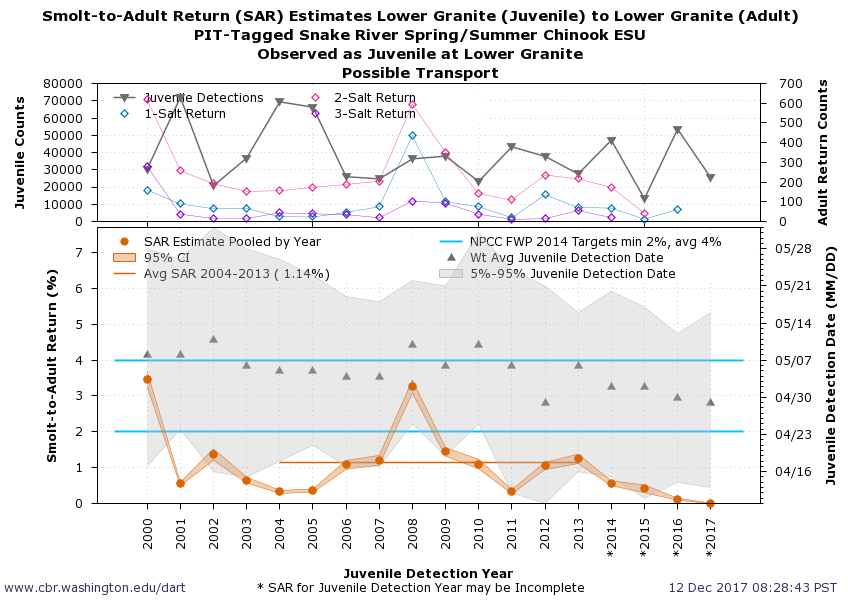

Snake River Spring/Summer Chinook

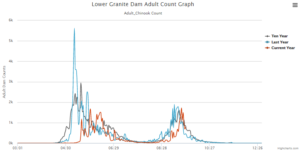

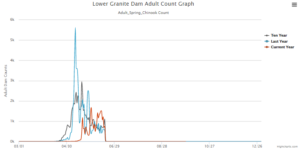

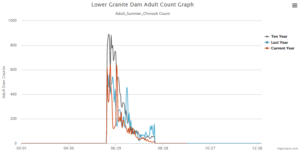

As noted above, 2015 was a disastrous year for spring and summer Chinook in the Columbia Basin. In 2016 the number of these fish that reached the Snake River at Ice Harbor Dam totaled 116,282. With the 2017 Chinook run over, as of August 29th that number is 44,762, a decline of 62%.

In late July 2017 the Idaho Department of Fish and Game reported adult spring Chinook numbers in Idaho would necessitate extraordinary measures to provide required brood stock to fill Idaho’s hatcheries.

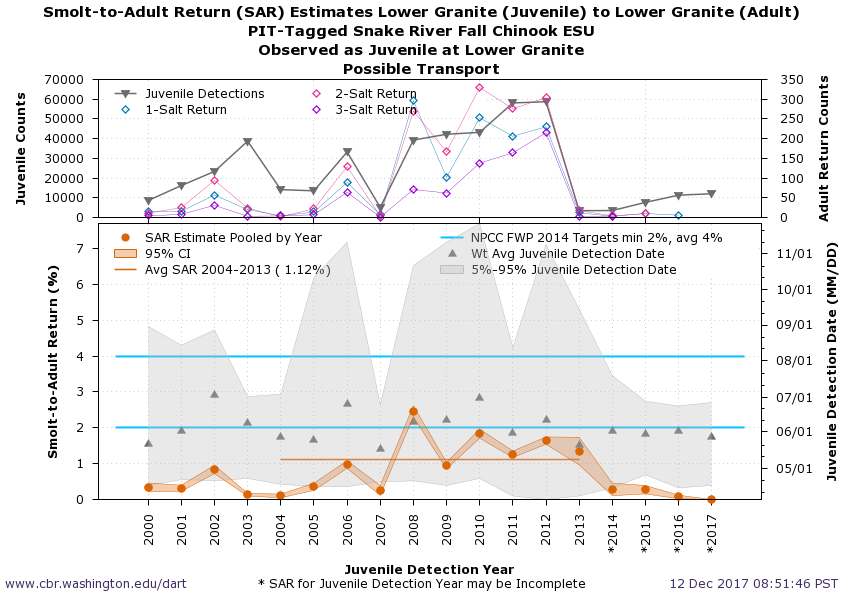

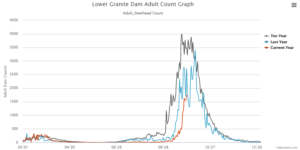

Snake River Steelhead

In 2016 the return of Snake River A-run steelhead was accurately described as dismal, with just 3,400 of these one-salt (one year in ocean) fish having crossed Lower Granite Dam by August 11th compared to a 10-year average of around 5,100 fish. By August 11, 2017, the number of A-run fish that had crossed Lower Granite was 393. As reported by Eric Barker of the Lewiston Morning Tribune on August 16, 2017, “the run is amongst the lowest on record at Bonneville, and the lowest ever at Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River.”

Snake River B-run steelhead typically spend two years in the ocean, and due to poor 2015 river and ocean conditions, 2017 was predicted to be a poor year for these steelies. While these fish are just beginning to move up the Columbia, run size predictions are worse than dismal. The number of the once famous wild B-run fish to pass Lower Granite dam is pegged at 770 fish. That prediction may need a downward adjustment.

The Pacific Northwest is currently experiencing a record-breaking heat wave that is impacting river temperatures. The Environmental Protection Agency prescribes a maximum water temperature of 68° F for salmon migration routes, but notes that rivers with “significant hydrologic alterations [like dams and reservoirs] may present additional problems even at 68°.” According to the EPA, multiple scientific studies have concluded water temperature of 70° “can result in severe infections and catastrophic outbreaks” in salmonids. A thermal block to migration begins forming at 71.6°. Water temperatures in the 72°–73.5° range characterize a lethal threshold when fish begin to die.

On August 10, 2017 seven of the eight dams on the lower Snake and lower Columbia had average daily forebay temperatures exceeding 70° F. Water temperatures at two dams were 73.5° F, and at one dam, 74.0° F. With a thermal block in place, at 73° F the term “poached salmon” takes on an entirely new meaning.

Collapse

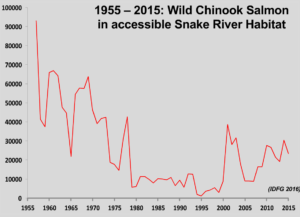

When Jared Diamond studied the collapse of entire societies, he learned that societies sometimes fail to perceive a problem “when it takes the form of a slow trend concealed by wide up-and-down fluctuations” sometimes referred to as “creeping normalcy” or, in salmon management, “shifting baselines.” The comparison of a current fish run with the preceding 10-year average provides an example of a shifting baseline that can camouflage a downward trend.

However, even when a significant problem is perceived, a society “often fails even to attempt to solve the problem” stated Diamond, frequently due to clashes of interest among people and special interest groups. “This is particularly the case when a small minority highly motivated by the prospect of profit—and often supported by government subsidies—competes with the majority who individually stand to suffer a relatively small loss insufficient to motivate them to protect their common interest.” This phenomenon is known as the tragedy of the commons, first described by Garrett Hardin in Science in 1968, wherein the parties who share a common resource find it in their individual best interest to exploit the resource until at some point the resource itself collapses.

In the present context, consider the Snake and Columbia Rivers and their tributaries and the fish therein as a giant, publicly owned commons, which in fact it is. Disaster struck the fish in 2015. In 2017 the combination of ocean and river conditions has created a fish run collapse. A collapse, says author and passionate salmon advocate David James Duncan, is simply extinction in slow motion.

Simultaneously, the plight of endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales that rely heavily on Columbia Basin salmon for survival share the salmon’s fate.

Who Will Save Idaho’s Threatened and Endangered Salmon and Steelhead?

Despite her tenacity, the Little Red Hen isn’t going to save the Snake River’s wild salmon and steelhead.

State Fish and Game Departments aren’t going to save our salmon and steelhead. These organizations are focused on hatchery production and setting seasons that keep sports anglers buying fishing licenses. In Idaho this year, with as few as 20 wild Clearwater steelhead available for “incidental take,” Idaho Department of Fish and Game is allowing a catch-and-release steelhead season.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE) is not going to save our salmon and steelhead. The Corps builds, operates, maintains and defends dams. For at least the past 20 years this federal agency has done everything possible to maintain the status quo on the lower Snake River. The Walla Walla District prominently highlights on its website the “Outstanding Value to the Nation” of the lower Snake River dams despite being confronted by 10 state and national conservation organizations calling out the Corps’ blatant misinformation in this propaganda piece. Under federal court order, the COE will spend the next 5 years and an estimated $70 million studying dam operations on the lower Snake and Columbia Rivers. The Corps is the agency that will decide whether the Lower Snake River dams should be breached. As was the case in the Corps’ 2002 Snake River Juvenile Salmon Migration Feasibility Study, the fix is already in.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries won’t save our threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead. This agency has produced twenty years of biological opinions (BiOps) that govern the operation of federal dams on the Columbia and lower Snake Rivers. Three federal judges over the same time period have declared NOAA’s Bi-Ops illegal, in part because NOAA Fisheries has ignored best science and protects the LSR dams at all costs.

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council won’t save our salmon and steelhead. This agency was created in major part to ensure the protection of anadromous fish in the Columbia River and its tributaries impacted by hydropower dams. The Council is supposed to “consider protection, mitigation, and enhancement of fish and wildlife and related spawning grounds and habitat, including sufficient quantities and qualities of flows for successful migration, survival and propagation of anadromous fish.” While Council members perhaps do “consider” fish protection, their actions make clear the production of hydropower has priority. The Council’s stated vision for its fish and wildlife program tells the tale. “The vision (an abundance, productive and diverse community of fish and wildlife) will be accomplished by protecting and restoring the natural ecological functions, habitats and biological diversity of the Columbia River System. Where impacts have irrevocably changed the ecosystem, the program will protect and enhance habitat and species assemblages compatible with the altered ecosystem.” (Emphasis added)

The US Fish and Wildlife Service won’t save our wild salmon and steelhead. This agency “provides a broad and flexible framework to facilitate conservation with a variety of stakeholders.” Thus USFWS lists and delists species and makes recommendations on what should be done to protect T & E species. However, the results are dependent on the actions of a myriad of other state and federal agencies, leaving the USFWS ultimately unaccountable for actual species recovery. Year after year the Smolt-to-Adult Return ratio (SAR) for wild Snake River salmon and steelhead remains below the level required for species maintenance, let alone to avoid extinction. Based on the past 20+ years, the USFWS will “facilitate conservation” until the last Lonesome Larry disappears.

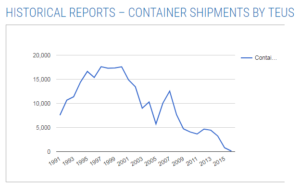

The Bonneville Power Administration won’t save our salmon and steelhead. With a surplus of power in the Pacific Northwest projected well into the future and BPA requesting a rate increase due to the lack of demand for its electricity, the agency continues to support the lower Snake River dams. BPA’s wholesale power price is now $33.75 per megawatt hour, while the price for the same power on the Northwest spot market is under $20. BPA’s financial reserves in 2007 stood at $917 million, and in 2017, just $21 million. Fifteen of the twenty-four turbines in the lower Snake River dams have exceeded their life expectancies, and rehabilitation of just the first three turbines has cost over $100 million to date. Northwest wind energy now produces nearly three times the electricity of all four Lower Snake River dams. Fully one-third of BPA’s price for power in 2016 is attributable to fish and game mitigation, supporting a failing program. Nevertheless, the agency’s support of the lower Snake River dams remains unwavering.

The Environmental Protection Agency won’t save Snake River salmon and steelhead. This federal agency is responsible for controlling pollution in the nation’s waterways, and temperature is a major pollutant. In 2003 the EPA completed a draft TMDL (Total Maximum Daily Load) study on the lower Snake River that demonstrated the single significant source of increased water temperature on the river is the solar radiation collected by the reservoirs behind the four dams, with each reservoir raising water temperature by up to 2 degrees Fahrenheit. Such a finding was anathema to the U.S. Corps of Engineers, the Bonneville Power Administration and the special interest groups that dominate the political support for the dams. The result was that the draft TMDL was soon buried. Today, fourteen years later, the EPA claims the completion of a final, actionable TMDL for the Snake and Columbia Rivers would be a difficult task requiring several additional years.

Congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers and five of her House colleagues won’t save the Snake River’s salmon and steelhead. These Northwest politicians and their political supporters can’t even get past their belief that our salmon and steelhead are achieving record-breaking runs. McMorris and her colleagues hope to mute the orders of a federal judge, stop any additional spill of water over the dams to help juvenile fish migrate to the sea, and halt any further alteration of any kind to the LSR dams without Congressional approval. They are betting the public can be duped by propaganda or won’t pay attention to the growing salmon crisis.

The Columbia-Snake River Irrigators Association has proposed a solution to the collapse of our wild salmon and steelhead —let them all die. They propose removing these fish from the protection of the Endangered Species Act and allowing wild fish to become extinct. Only one dam on the lower Snake, Ice Harbor, provides irrigation, and to fewer than 20 farms.

A comment about ocean conditions is appropriate here. Ocean conditions will emerge on the websites of the agencies and special interest groups that support the continued existence of the lower Snake River Dams as the shorthand explanation for 2017’s collapsing Snake River fish runs. On August 24, 2017 Idaho Department of Fish and Game Clearwater Fisheries Regional Manager Joe Dupont published an analysis lending credence to this position. Dupont included an important caveat to his analysis. “However, I need to emphasize that continued improvements to spawning and rearing habitat and the migratory corridor can make a difference in salmon and steelhead returns. In fact, I would argue that in years like this, if we had better spawning, rearing, and migratory conditions, it could buffer the poor ocean conditions to the point that we could still provide harvest fisheries in Idaho, and wild fish would not be threatened of going extinct.” (Emphasis added) The reader should be aware that Idaho rivers and streams include over 5000 miles of salmon and steelhead spawning and rearing habitat, much of it in pristine condition, leaving the migratory corridor the principal issue. Also noteworthy is the fact the State of Idaho is a co-defendant in the latest legal challenge to the Biological Opinion (BiOp) governing the operation of the dams on the Columbia and lower Snake Rivers. Idaho is thus defending the status quo on dam operations, which federal Judge Michael H. Simon acknowledged, and the record clearly demonstrates, are imperiling threatened and endangered Idaho salmon and steelhead.

Will anyone save our wild Snake River salmon and steelhead and the orcas of the Salish Sea?

In Collapse, Diamond identifies three approaches that have proven successful in the past to preserve a commons resource. First, a government can step in to enforce harvest quotas and take other actions necessary to preserve the resource. In the case of Snake River salmon and steelhead, a host of government agencies have spent 20+ years and billions of dollars on the recovery of Snake River threatened and endangered fish. All species continue to decline. The Southern Resident Killer Whales are likewise an endangered species, suffering from a lack of a major portion of their diet, Columbia Basin Chinook salmon. As noted above, government agencies have devoted much time and treasure to maintaining the status quo on the lower Snake River and continue to do so today.

Privatization of a commons resource is a second possible solution, based on the hope that private owners would take a long-term perspective and be good stewards of the resource in order to protect their own interests. This solution is not possible, however, when the resource cannot be divided, which is the case with migratory fish and game.

A third possible solution, which Diamond acknowledged as the most difficult, requires that consumers of the resource recognize their common interests and actively intercede. According to Diamond, “That is likely to happen only if a whole series of conditions is met: the consumers form a homogeneous group; they have learned to trust and communicate with each other; they expect to share a common future and to pass on the resource to their heirs; they are capable of and permitted to organize and police themselves; and the boundaries of the resource and of its pool of consumers are well defined.”

If Diamond’s analysis is correct, saving Snake River wild salmon and steelhead requires an aggressive mass movement, most likely originating in the Pacific Northwest, of people who refuse to see our river and ocean commons stripped of the iconic species that help define who we are and where we live. While the removal of the lower Snake River dams is a critical element in Snake River Basin fish recovery and can provide a focus for civil action, returning the lower Snake to a more natural flow will not be sufficient. Needed is an entirely new salmon management effort based not on the failed industrialization of salmon production in concrete tanks but the stitching together of the ecological requirements of salmon and steelhead life cycles.

Meanwhile, the great fisheries commons we call the waters of the lower Snake, the Grande Ronde, the Imnaha, the Clearwater, even the namesake Salmon River itself, is disappearing. The scientific community advises that the warming of the planet will continue to make this situation worse.

Whatever individuals and organizations throughout the Pacific Northwest who care about Snake River salmon and steelhead are now doing is not enough. Whatever supporters of Southern Resident Killer Whales are doing now to protect a critical food source for these orcas is not enough. Concern without anger is insufficient to save our wild Snake River salmon and steelhead; anger without outrage belittles the truth; outrage without action is a sure path to species extinction.

Linwood Laughy Kooskia, Idaho 83539 lochsalaughy@yahoo.com