Port of Lewiston loses 100 percent of its container traffic

Posted /Uncategorized

Commercial shipping on the lower Snake River continues to decline–dramatically.

The Port of Lewiston confirmed yesterday and officially announced today that it was indefinitely suspending container shipments after an international shipper said it would no longer use the Port of Portland on the Columbia River downstream. The Port of Lewiston’s business had constituted the only containerized freight traffic on the lower Snake River.

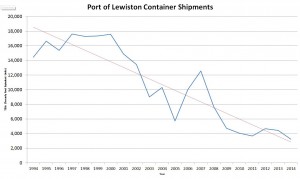

Container shipments from the Port of Lewiston peaked in 1997 and have been on a dramatic and steady decline ever since. This week’s events underscore how inconsequential lower Snake River shipping has become as port managers scramble for alternatives, including the possibility of shipping via an existing railroad.

The following news article appeared in today’s Lewiston Morning Tribune.

Port container traffic on hold indefinitely

By ELAINE WILLIAMS of the Tribune

The permanent withdrawal of a key overseas shipper from the Port of Portland has put container traffic at Idaho’s only seaport on hold indefinitely for the first time since it started in 1978.

Hapag-Lloyd confirmed Tuesday it’s no longer calling on the Port of Portland and will serve its customers through other locations, such as the Port of Tacoma, according to a prepared statement from the German-based shipper.

“We regret any inconveniences for customers and also any negative impact on the port. Our offices are prepared to offer alternative options.”

Hapag-Lloyd handled the ocean going portion of the journey for more than 90 percent of the containers that originated in Lewiston.

The only remaining container carrier at the Port of Portland is Westwood, and it’s unlikely it will be able to absorb Hapag-Lloyd’s customers from Lewiston since it visits different destinations, said Lewiston Port Manager David Doeringsfeld.

“At this point in time, the Port of Lewiston is not shipping any containers on water,” he said.

Doeringsfeld said he and the port commissioners are trying to grasp what the effect will be and to create a strategy to respond. They will discuss the issue at their meeting today.

The port employs seven people, four at the container yard and three in the administrative office, including one part-time worker.

Doeringsfeld declined to discuss what will become of the employees connected to the container dock.

The container yard was projected to generate about $4,000 in revenue this year after expenses of about $295,000, Doeringsfeld said. In both instances, those figures are roughly half what was originally forecast because the port didn’t predict a slowdown of labor on the West Coast during a contract negotiation where a tentative agreement has been reached, Doeringsfeld said.

Costs would have been more except the port found other jobs for container employees to complete while containers weren’t moving, such as performing maintenance on port-owned buildings.

When the work the employees were doing wasn’t related to the container yard, it was charged to other areas of the budget, Doeringsfeld said.

Those figures come from a $1.9 million budget where gross revenue from the container dock is one of the largest sources of income. The port had expected about $450,000 each from rentals and property taxes as well as $260,000 from Inland 465, a huge warehouse in this fiscal year.

What the port can do for its customers who mostly ship dried peas and lentils is still being determined, Doeringsfeld said.

One possibility is shifting that business to rail, but making the service available is complicated. The Lewiston-Clarkston Valley’s only line, the Great Northwest Railroad, is a short line that would have to negotiate agreements with the carriers it connects with in Washington – Union Pacific or Burlington Northern Santa Fe.

“That’s something that takes months, not weeks,” Doeringsfeld said.

The port also is exploring the possibility of recruiting other business to its container dock, but has no signed contracts at this time, Doeringsfeld said.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the dock will remain inactive, since those agreements are often finalized about 30 days in advance, Doeringsfeld said.

Even though business at the container dock has come to a halt, the port still believes its investment of $2.8 million to more than double the length of its container dock with $1.3 million in federal money was a good choice, Doeringsfeld said. “We will continue to market this asset to promote job creation.”

Losing the container business is a blow, but Doeringsfeld said containers represent only about 15 percent of the tonnage shipped from the Port of Lewiston. The remainder is bulk grain that leaves the Lewis Clark Terminal at the Port of Lewiston.

Overall barge shipping on the Snake and Columbia rivers continues to play an important role in the economy of the Lewiston-Clarkston Valley, Doeringsfeld said.

Clearwater Paper, for instance, barges chips and sawdust for its Lewiston mill to the Port of Wilma just west of Clarkston from Columbia City, downriver of the Portland area.

As the Port of Lewiston determines its next move, many are watching closely, including environmentalists.

Taxpayer subsidies play an increasingly important role at the Port of Lewiston, said Greg Stahl, a spokesman for Idaho Rivers United in Boise, which supports removing the four lower Snake River dams.

“How much economic benefit is this really generating for the amount of outlay?” Stahl said. “In any free-market scenario, it appears the port wouldn’t even exist, at least at this point.”