The ‘prosperity’ from Lower Snake River dams

Posted /Uncategorized

Opinion piece in the Moscow/Pullman Daily News

His View: The ‘prosperity’ from Lower Snake River dams

By Linwood Laughy

Nov 7, 2016

In 1973 residents of Idaho’s Clearwater Valley were told their prospects for prosperity rose with each foot of slackwater filling the reservoir behind the Lower Granite Dam. Waterborne commerce would flourish, and Idaho’s only “seaport” would become the economic engine of the Clearwater Valley.

The Idaho Department of Labor generates economic data on Idaho’s six geographic regions. How does north central Idaho, which includes Moscow and Lewiston, compare with the other regions and the state as a whole 1994-2014?

- Job growth: The number of jobs across the state during this period grew 39.8 percent. In the southwest region – call it Boise, the growth rate was 50.6 percent; in the northern region or Coeur d’Alene, 44.8 percent. South central or Twin Falls was 39.2 percent; Eastern or Idaho Falls was 37.7 percent. Southeast or Pocatello trailed at 18.8 percent, Job growth in north central Idaho – Lewiston and Moscow – was just 6.1 percent.

- Labor force: Idaho’s labor force grew 37.4 percent. Boise edged Idaho Falls 53.4 percent to 49.5 percent. Coeur d’Alene posted growth of 33.3 percent. Pocatello and Twin Falls hovered around 20 percent. Lewiston/Moscow came in a distant last at 1.1 percent.

- Private sector employers: Idaho increased by 42.1 percent. Idaho Falls at 58.9 percent topped Boise at 54 percent growth. The growth in Coeur d’Alene, Twin Falls and Pocatello ranged from 30.9 percent to 35.4 percent. Lewiston/Moscow grew just 4.2 percent.

- Leisure and hospitality: Growth in this major industry was 40 percent to 69 percent in three regions. One region experienced a 25 percent gain, one only 13 percent. Lewiston/Moscow came in last with 7 percent growth.

- Manufacturing: Lewiston/Moscow’s manufacturing jobs declined steadily from 1994 to 2004 (-21 percent), climbed slightly to -17 percent by 2008, and by 2014 had returned to nearly the same level as existed in 1994.

- Population growth: According to U.S. Census data, from 1993 to 2013 Idaho’s population grew by 45.5 percent. Lewiston’s population grew just 8.5 percent and Moscow’s 28.7 percent.

So, what role is waterborne commerce playing in the regional economy?

In its 2002 Lower Snake River Juvenile Salmon Migration Feasibility Study, the Army Corps of Engineers claimed that shipping volume on the lower Snake River would increase in all five freight categories. The Corps’ projections have proven highly exaggerated in every category at every benchmark year. The Corps now categorizes the lower Snake as a waterway of “negligible use.”

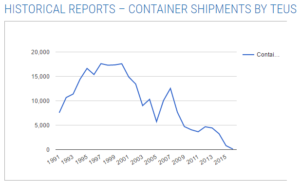

Total freight volume on the lower Snake’s reservoirs over the past 15 years has dropped by nearly half. Container shipping has declined 99 percent, with much of that decline occurring well before container shippers abandoned the Port of Portland in 2015. Barges no longer ship lumber or paper, and little if any pulse crops. Even grain volume, nearly the only commodity still shipped on the Snake, has declined by 45 percent since 2000. None of the major employers in the region ship any product by barge, and most major imports, such as chemicals for making paper and fertilizer, arrive by rail.

Federal judges have repeatedly found the lower Snake dams are being operated in violation of federal law, and threatened and endangered wild salmon and steelhead remain in peril. Over $600 million spent “fixing” the dams has not improved juvenile fish survival. Fish mitigation costs on the Columbia and Snake Rivers have exceeded $14 billion with no species recovery in sight. The four lower Snake River dams now produce only 3 percent of the Pacific Northwest’s electrical energy and only 6.5 percent of the Northwest’s hydropower.

Economic, biological, legal and climate realities cry for a change in the status quo. Citizens and politicians can embrace such change – turning the restoration of the lower Snake River into a major economic and ecological benefit – or continue down a path of high taxpayer and ratepayer costs, the likely extinction of Idaho’s sockeye salmon, continued economic uncertainty and stagnant economic growth.

Linwood Laughy, activist, author, outfitter and former educator, lives near Kooskia beside the Middlefork of the Clearwater River.